Have you ever stood in a pharmacy and tried to decide whether a brand-name or generic product is better? I recently experienced the headache of choosing from a sea of painkillers at RiteAid. The emergency department had recommended Motrin. RiteAid carried both Motrin and half a dozen generic brands containing ibuprofen, the active ingredient in Motrin.

Research shows no appreciable difference in the performance of brand-name and generic painkillers. I was hungry and wanted to go home. Consequently, I selected a bottle of the cheapest generic Ibuprofen and headed for the checkout.

Typically though, the lowest price is not the overriding factor for a consumer weighing a purchase.

For a moment, imagine yourself as an ag mechanic. You use hand tools daily to repair equipment and please your customers. Yesterday, your favorite screwdriver snapped as you pried on a stubborn pulley.

So today, you’re standing in the store comparing screwdrivers. The store displays three identically sized screwdrivers. Their prices are $3.99, $10.99, and $19.99. Which one will you buy?

You instinctively think back to that tight pulley. This screwdriver needs to withstand heavy-duty wear and tear every day. Certainly, you won’t even consider the $3.99 screwdriver. It will probably break the first time you use it. The $10.99 one might be okay, but you really don’t want to need a replacement in six weeks. Why not go for the best right away and pay $19.99? That sounds logical. Almost any other mechanic in your situation would choose the same screwdriver.

Here’s the fascinating thing–the only information I have told you about the screwdrivers is their prices. How do you know that the $19.99 screwdriver is the best? You know nothing about the quality, color, size, or warranty. Yet you feel comfortable making that decision knowing only the price.

An item’s price strongly impacts our perception of its value. We often infer the quality of goods and services from their published price. Of course, the correlation between price and quality is far more complex than this. A wise consumer also considers product features, customer reviews, brand reputation, and warranty before purchasing. But, especially when other information about the product is limited, its price is the single most significant indicator of value.

What does this knowledge mean to you as a business owner? How can you take this information into account as you set your prices?

Two Methods of Pricing

1. Cost-Plus Pricing

Let’s look at two common methods of establishing prices: cost-plus and value-based.

A simple cost-plus pricing formula would look like this:

Material Cost + Labor Cost + Overhead Allowance + Profit Allowance = Price

The cost-plus pricing method is a good way to ensure that the price you charge will cover your expenses and generate a profit. In real life, the cost-plus formula for a screwdriver might look like this:

$3.20 (Material Cost) + $1.60 (Labor Cost) + $1.20 (Overhead Allowance) + $2.00 Profit Allowance = $8.00 (Price)

2. Value-Based Pricing

Value-based pricing sets the price by comparing the product/service package to similar product/service packages on the market. To establish pricing, list your significant points of value.

Examples of points of value include:

- Quality

- Ease of use

- Comfort

- Aesthetics

- Size

- Capacity

- Options

- Availability

- Service (before and after the sale)

- Warranty

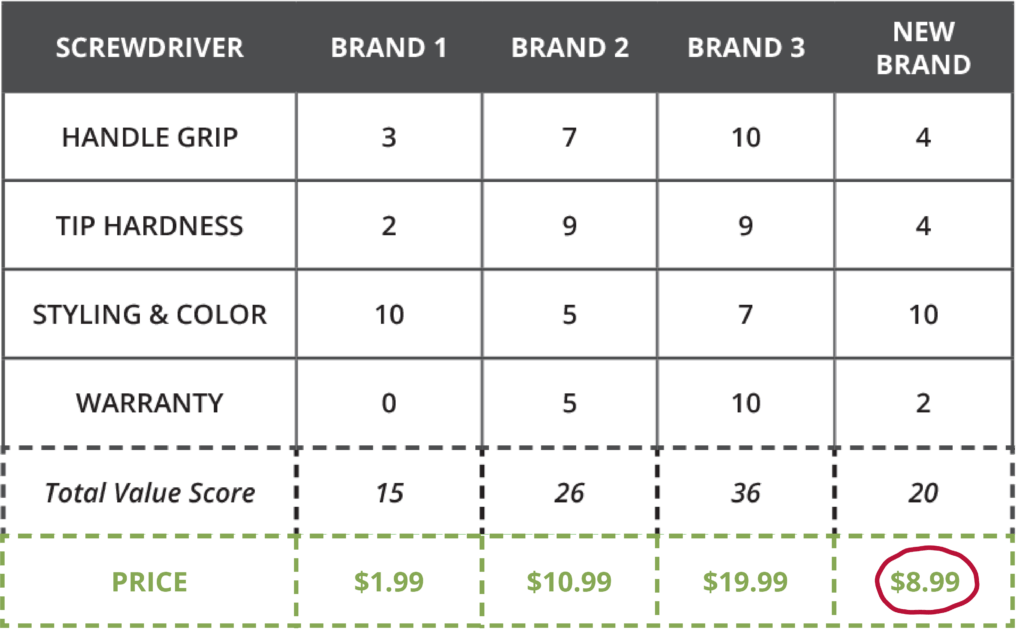

For each point of value, assign a score between 1 and 10. Comparing the total score for similar products reveals how they rank in value. The chart below shows a sample value-based pricing model for a company considering a niche in the screwdriver market.

Comparing points of value of similar products also reveals gaps in the product lineup. A gap is an opportunity for some entrepreneur to fill.

Where does the opportunity exist in this screwdriver market? The low-priced $3.99 screwdriver attracts a six-year-old boy with mechanical aspirations. The $10.99 screwdriver satisfies the shade-tree mechanics or do-it-yourselfer. The $19.99 model meets the needs of a professional mechanic.

But examine the mid-range of pricing. What could fill that gap between the $3.99 and $10.99 models? How about a screwdriver for the housewife’s kitchen drawer? Wouldn’t an $8.99 price appeal, especially if it included feminine styling and colors? Add a small warranty, and you have a winner.

Notice that the relationship between the total value and the price is somewhat loose. Value-based pricing is not a strict formula. Instead, it provides a guideline for what the market would expect to pay for the value provided.

Which Pricing Method Should You Use?

Which method should you use to establish pricing — cost-plus or value-based? You should consider both.

First, calculate the cost-plus price. This is the minimum price that you can afford to charge. Then, determine the value-based price. If the value-based price is higher, the decision is easy. Use the value-based price. If the cost-plus price is higher, you have a problem. The market will not bear what you need to charge.

You can address this one of two ways.

- Find a way to lower costs and/or increase the value of the product/service package.

- Discard the product/service package and look for a better opportunity.

If the value-based pricing model yields a price higher than the cost-plus calculation, you may think, “I’ll provide more value than the competition and charge a lower price. That will be attractive to customers and generate a lot more sales.” That is a good theory, but it does not always work that way in practice.

The screwdriver pricing scenario in the hardware store demonstrates our tendency to believe in the value that the price indicates. You misinform the customer when you set a price that is out of line with the actual value. Misinformation is a disservice to both the customer and to you. People are willing to pay for what they want and usually believe–“You get what you pay for.”

The best practice is to be realistic with the value of your offering and charge accordingly. Sell more by setting your pricing correctly. Price is the single most significant indicator of value.

Does This Work in the Real World?

Consider this real-life story. (Names and details have been changed.)

When Silas Kauffman and his brother Cecil moved their family to a church extension, they left behind a successful business, manufacturing and retailing hardwood furniture.

Given their business experience and woodworking knowledge, the Kauffmans decided to build a similar furniture business. Judging by the living standard in their new neighborhood, the brothers guessed that their upper-middle-class neighbors would be eager to buy high-quality wood furniture.

Silas and Cecil got their business off to a fair start and reached moderate profitability, but something didn’t seem right.

Many folks visited the sales floor. They browsed the showroom—rubbing their palms across the furniture tops, gazing admiringly at the styling, and asking about the quality of the materials and building techniques. Then, after rechecking the price, they would slowly walk out—still looking around the showroom with interest. The Kauffmans were missing too many potential sales.

The Kauffmans wondered, “What is going on in these customers’ minds?” They began asking questions. Soon, they learned that many of their prospects were comparing the Kauffmans’ products with a high-priced national brand that had a longstanding reputation for high-quality furniture.

The Kauffmans’ prices were much lower than the prices of the national brand. Silas and Cecil understood something about the way pricing communicates value. They took a brave step. They raised their prices by 30-40%.

What do you think happened? Did higher prices turn away more people without buying? No! Furniture sales soared! At the lower pricing level, many people walked out because they “knew” they could not buy the quality they wanted for such a low price. With the higher price point, customers could believe they would get the high-quality furniture they wanted.

Block out time in your schedule to evaluate your pricing with a value-based pricing model. Remember, price is the single largest indicator of value.