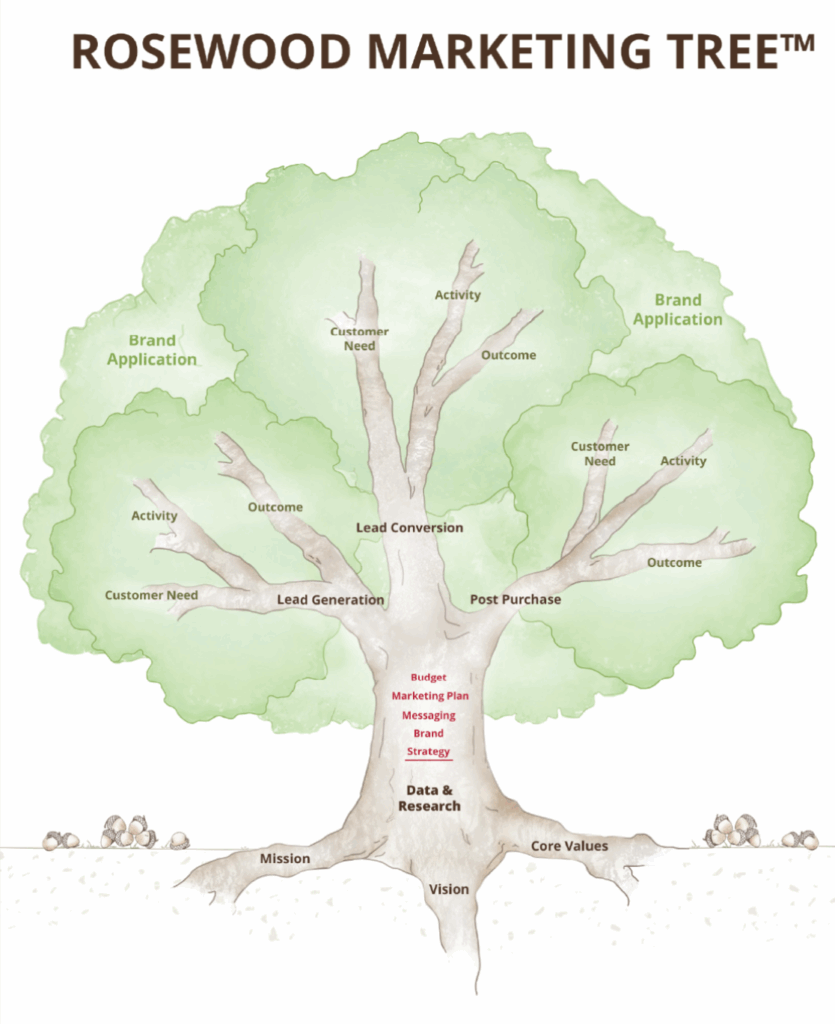

Components of the Marketing Tree: Trunk – Research

Father sighed. Eight-year-old Marcus and ten-year-old Marla were fighting again – this time over a banana, the last one of the bunch. Silently, Father cut the banana in half, giving each child a piece.

Imagine Father’s surprise when he discovered a peeled but uneaten banana lying on the porch a few minutes later. Those children! Who had thrown that half away, and why? Father sighed again.

Finding Marla happily eating her portion, he went searching for Marcus. He found him polishing his shoes with half a banana peel. “This works!” Marcus informed with a grin, finishing his buffing with a flourish. “I had read that you can use peels to do this, and it works!”

“You only wanted the peel?” Father stared at his son.

“Yeah. I don’t care that much for bananas, but from now on, I want the peels for my shoes.”

With a little more research and a little less assumption, Father could have brokered the perfect deal and taught a valuable lesson in the process. Marcus only wanted the peel to experiment with; Marla only wanted the edible part.

The purpose of research

Why research? Understanding a customer’s problems and needs is crucial for any business. Effective companies figure out who wants a “banana” and who wants the “peel.” Then they create products and services that fulfill those needs.

Furthermore, most companies have competitors vying for the same customers. The graphic below helps us visualize the often crowded marketplace. Research helps us find some “green grass” where we can root and grow without being crowded out. “Green grass” is often discovered by truly understanding what the customer wants.

A third reason for conducting research is to cut through common assumptions. To assume is to “take as granted or true though not proved.” This was Father’s mistake in the banana debacle. In business, assumptions are frequently to blame for squandered opportunity, effort, and capital.

Assuming that customers care about lower prices is common; in reality, they often care more about solving their problems. Or we may assume that our clients want better quality in our products, but they may actually prefer better service and support. Even if you provide great customer service, how do you know that your customer doesn’t want to be served differently?

We assume our customers know their needs. What if they need to be educated about their needs, and what can be done to solve them? We believe that if we outperform our competitors, we will secure the business. However, if our customers actually want something different, it doesn’t matter how well we stack up against our competitors.

Trends change, as do needs and wants. Research keeps us at the forefront of the dynamic business environment. Sam Walton said, “You can’t just keep doing what works one time: everything around you is changing.” Split-level houses with popcorn ceilings are a thing of the past. Research enables us to understand the current environment and remain relevant to our customers.

How to do research

Many businessmen regard research with a bit of skepticism. After all, it takes time and resources. And research itself is often viewed as a bit mysterious: “What am I to be researching? Or “I’m getting along pretty well without chasing down information I don’t need anyway.”

The best research advice I ever got in my life came from business consultant David Sauder, “Ask questions.” Questions are how children learn, and it shouldn’t stop with childhood! “Wisdom is gained by asking, and a prudent question is one-half of wisdom,” Francis Bacon. “Wisdom is profitable to direct.” (Ecc. 10:10).

There are different levels and types of research.

1. First is what could be called desktop research.

This type of research is conducted from your desk–it involves pulling up government data, such as demographics. It might include determining the average age of the residents in a section of town you are servicing, or learning their average income. There’s a wealth of information compiled these days about subjects relevant to your industry.

A builder may want to know the number of new housing starts in your county, which can be determined by the number of new building permits issued or the number of electrical meters installed in the last quarter.

Alternatively, you may want to know how many cabinet shops or dental offices are located in a specific area. How many square feet of grocery outlets are needed to support a particular population number, and does the area in focus have more or less than the national averages?

This is big picture information that can be researched to determine overarching questions. Desktop research can be characterized as the overflight of an eagle, seeing the big picture.

Here’s an illustration of 360-degree desktop research.

Harry Wong tells of Al Sisson, “who ran the corner service station and was my mechanic for over 20 years. He was good at fixing cars and honest to boot. I got some insight into why he was so good when I was in his waiting room one day. There was a melange of automotive magazines, mostly filled with ads from automotive parts houses, strewn on a table. I said to Al, ‘You read this stuff?”’ He said, in his brusque voice, ‘I wish they would stop sending me that garbage.’ But then he looked at me over his glasses and said authoritatively, like a mentor who knew he was right, ‘You bet I read it. If I didn’t, I’d go broke!’

Al Sisson was a professional. He enhanced his own life without anyone telling him what to do. This is why many [businessmen] are bankrupt and the Al Sissons are not. Knowledge is power.”2

Businessmen need to read industry news and stay abreast with developments in their customers’ worlds.

2. Secondly, immersive research is more characteristic of a ground-based hunter, such as a ferret or snake.

Immersive research involves conducting face-to-face visits and speaking directly with clients about their experiences in their environments. The router bit salesman is actually on the shop floor, watching the process and even running the machine himself to better understand his client’s experience. It involves visiting your competition: coffee shop owners often drink coffee in other people’s shops during their immersive research.

Employees usually have a perspective as well that needs to be tapped to stay relevant—workers in the business know things the manager or owner might not know because they are out in the field and experiencing realities firsthand.

3. A third type of research is experimentation.

It is testing products and trying different things to see what works best. It is modifying a product and doing field testing. It’s trying different advertising venues and tracking the results. It’s asking the client (in optometrist style), “A or B?” “B or C?” Or, as with paint samples: this shade or one lighter? It is trying different packaging, different wording, or different photos to find the winner.

“Shoot bullets before cannonballs,” advises Jim Collins. In the experimentation process, don’t get over-invested in any one new idea. Small, low-risk steps coupled with periodic adjustments based on testing are a safer way to research possibilities. Once you know you’re hitting the target, then bring in the big guns, investing significant effort, tooling, or marketing to make the idea boom.

As shown in the illustration above, some research is quite open-ended, extending in all directions.

For example, Mike, the owner of Mike’s Meats, senses they have plateaued in the services they offer and the freshness with which they used to approach business. But he can’t lay his finger on what to do about it.

Well, Mrs. Chatty, one of the regulars at Mike’s Meats, leaned on the counter one day and talked about how she loved watching this family operation grow. And she hoped to see more growth and innovation in the future. Mike seized the opportunity and began asking questions: non-directional, open-ended questions. “What is something you would like to see here that we currently don’t do, or a service we don’t offer?” “If there is one thing you would change about us to make it a better experience, what would it be?”

Out of that came a few good ideas–Mrs. Chatty took Mike for a mind-stretching ride. “Refresh the retail space (it’s a little underwhelming compared to the product you are selling).” “Showcase your products by free samples, maybe once a week or once a month.” “Have a large section of grilling equipment for sale.” “Oh, a sit-down eatery with everything from hot dogs to steaks on the menu would be nice–and don’t forget your incredible pork chops!”

All these free, brand-new ideas were Mike’s reward for asking a non-directional, open-ended 360-degree question.

Mike has a friend who owns a stove and fireplace store. In addition to indoor heating equipment, he also has a vast array of outdoor cooking equipment. Mike made a mental note to pick his brain about grilling enthusiasts, grills, and grilling accessories. This is an example of leveraging a parallel industry.

One of Mike’s customers is a pole-barn builder. He understands the people who raise their own livestock, as they are primarily his clients. Again, Mike chats with him to learn more about these farmers.

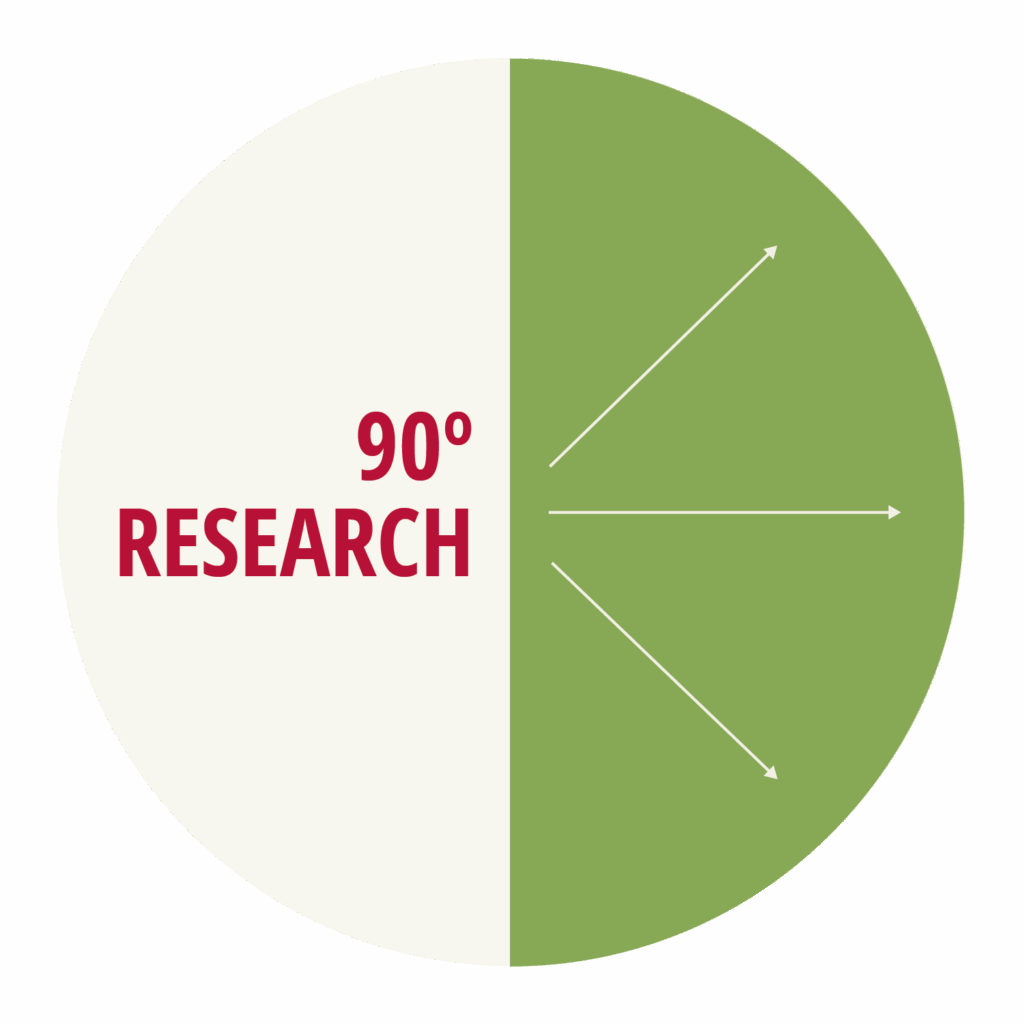

A second type of question is more directional, more focused. It isn’t grasping in all directions, but is represented in the illustration as a 90-degree perspective. While the questions being researched are still open-ended, they have a more specific goal. For example, Mike agrees with Mrs. Chatty about his retail section, and he is ready to take action to remedy it. But he has no idea where to begin.

It’s time for Mike to ask some directional, open-ended questions about his retail area. Mike might learn a lot by simply asking, “Hey, what can I do to make this place feel better? Do you have any ideas?”

And out of that conversation with several customers, Mike learned that using more rough-sawn wood and less paint, incorporating warm lighting instead of cool fluorescent tones, and reconfiguring the layout of the checkout and display cases would make a better presentation.

Another helpful customer was a lighting engineer and recommended (for free, over snack sticks) a specific type of lighting strategy that would transform the feel of the space.

On a whim, Mike stopped in to visit other similar stores and asked himself two questions: (1) “Do I like what I’m seeing?” and (2) “Why or why not?”

Mike began observing customer behavior in the store. He noticed customers would often pick up multiple cuts of meat before making their choice. With a few questions, he discovered that the label font size was too small for these customers to read without picking up the package.

This focused research allows Mike to drill deeper into the idea that his 360-degree study produced. He’s focused now on retail ambiance and how to achieve it. That’s 90-degree directional research, but still open-ended.

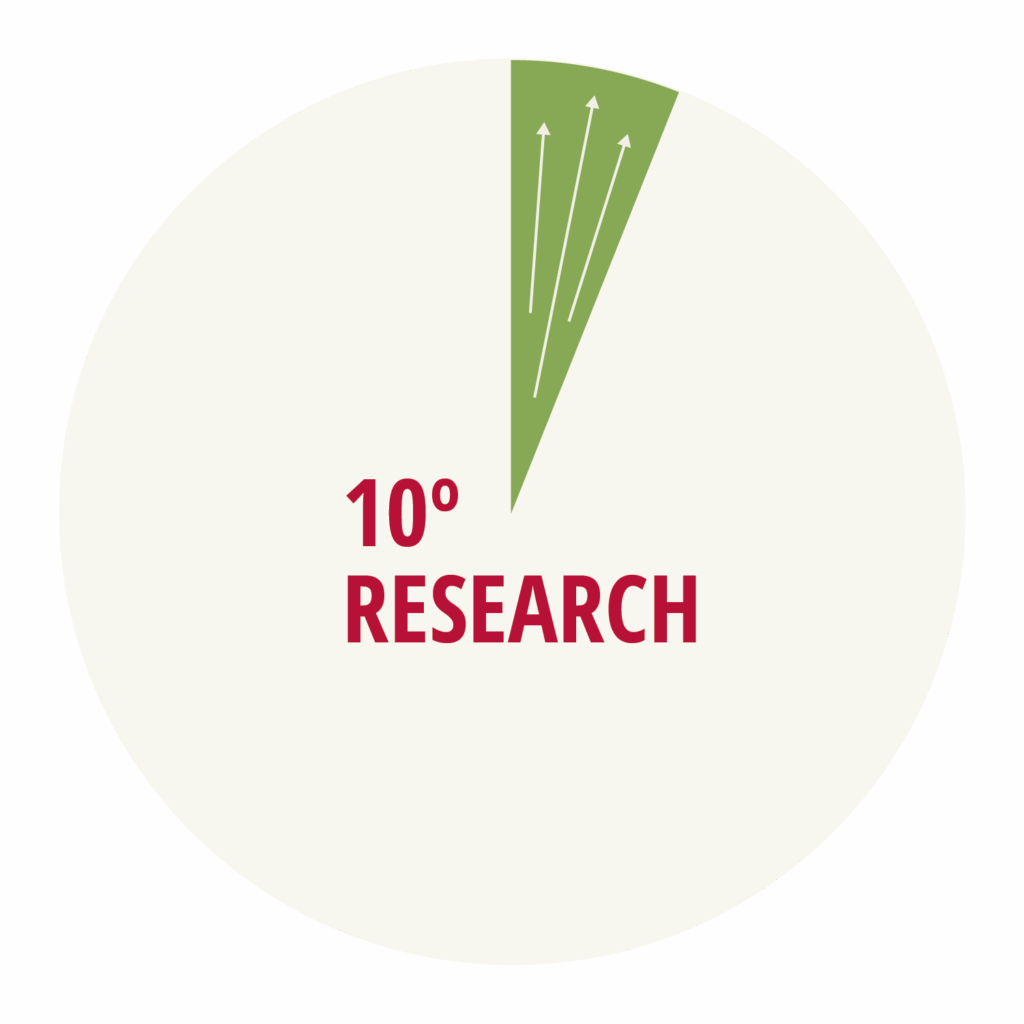

This graphic shows a third type of question—the focused 10-degree question. This type of research is focused on a single, well-defined issue. It is narrowed down to a multiple-choice or either/or format. Once properly researched and answered, the course of action narrows increasingly to a single-degree compass setting.

Mike had been experimenting with differently sized burger patties, but what he wanted to know was whether people preferred a half-pound, third-pound, or quarter-pound burger. His machine was capable of forming all three sizes, but he sensed that he needed a standard size; if folks wanted something different, he could make it as a custom option. So he conducted a poll of his customers, asking which of the three sizes displayed in the checkout cooler was their preference. He defined the issue, gave three choices, and established a standard size.

Making research work

Here are some other ways Mike’s Meats harnesses the power of real research to know what to do and how to do it. Mike expensed these activities out of his marketing budget.

Picking up on and combining the ideas of free samples and a sit-down eatery, Mike decided to explore these intriguing customer suggestions.

Starting small, Mike took his grill to the Farmer’s Market on Saturday and invested in a small canopy bearing “Mike’s Meats” on the fringe. For the first two weeks, he gave out bite-sized meat skewers for free, with the only cost being a survey response to choose between two flavors, “A or B.” In short order, a long line of hopefuls formed to receive their free samples. It didn’t take long to transition from free samples into a full-blown, 10” kabob, this time available at current market value. The idea of an eatery seemed closer than Mike had thought possible. And he was also gaining a great deal of data on customer preferences.

In a few weeks, free snack stick samples were available, again the “fee” was giving your preference between “A or B”. You could buy your own to take with you, of course. Later, it was mini-hamburgers on slider buns. “Choice A” was just your standard burger; “B” was a jalapeño/bacon/cheddar burger. Shortly after this research, Mikes Meats was cranking out more specialty burgers of this type than he would have thought possible. It had all started with research.

By now, Mike was seriously considering a food trailer, but he wanted to ask a few more 90-degree type questions of his customers first.

Mike conducted another survey to determine preferences for customers who had a whole beef or deer processed for their freezer. He asked targeted questions, such as “From a 250-pound beef, how many pounds of roasts would you like, how much ground beef, and how thick would you prefer your steaks?” Through this process, standards were developed, which significantly streamlined the workflow.

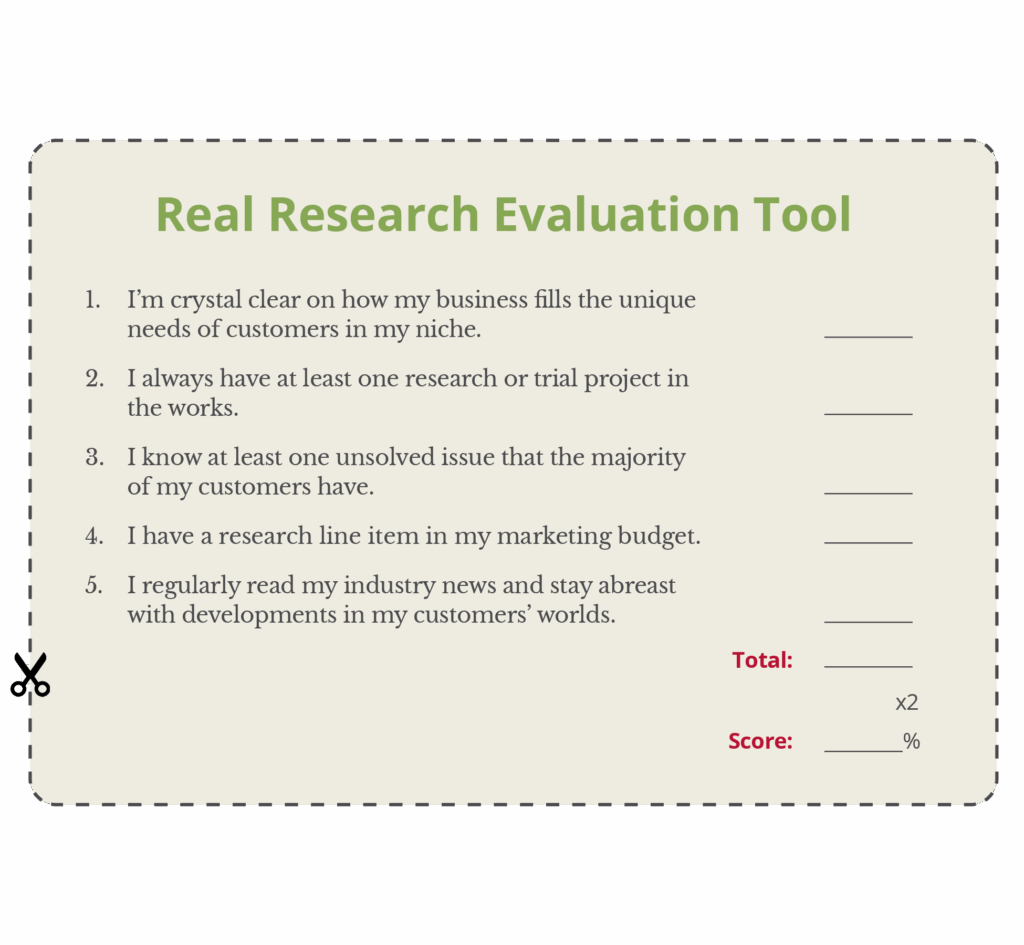

Evaluate your business

How well do you use the power of real research in your business?

Use the tool below to evaluate this question. For each of the questions, rate yourself on a scale of 1 – 10, 10 being the highest. Then total your points and multiply by two to get a percentage score.

Notes:

1. Great by Choice, Jim Collins and Morten Hansen, published by Harper Business. Page 200

2. The First Days of School, Harry Wong and Rosemary Wong, published by Harry K. Wong Publications, 2005, Page 277