When Mike left Ameripac Locker to start his own business venture, it didn’t take long before he was scratching his head about pricing. Setting prices was something he didn’t have to think through as an employee, where his main function was simply cutting meat.

Being a consumer himself, he knew that pricing conveyed a great deal. For example, he knew the difference between a $3.99 knife, a $15.99 knife, and a $39.99 knife. For deboning a beef, Mike knew which knife to purchase by price alone.

Mike also frequently scanned the meat snack sticks in the gas station convenience store, noting that the prices communicated quite a bit about the meat sticks for sale.

It was Mike’s turn to price his products and services at the newly formed Mike’s Meats. But several years later, the job of pricing hasn’t gone away, and he still scratches his head.

What are the key components of pricing? What does Mike need to understand about purposeful pricing?

The price level customers are willing to pay is directly linked to the value and size of the problems solved.

Folks will pay more if the value is there. Successful pricing considers the needs of the customer and the relief or satisfaction that the purchase provides.

For example, most of us are unaware of the costs a dentist considers when determining the price of a filling or root canal. However, we give sizable amounts of money to have the tooth pain removed so life can be lived pain-free, and so we can enjoy eating again. The lifestyles and buildings of dentists who have been in practice for a while suggest that more than simply “cost plus” pricing determined their fee structure.

In his book The Personal MBA, Josh Kaufman highlights value-based pricing as the primary guide to setting prices. He writes, “Use the other methods as a baseline, but focus on discovering how much your offer is worth to the party you hope to sell it to, then set your price appropriately.”

Of course, we can’t just ignore our costs when establishing pricing; the cost of a product or service must be calculated to help determine the price. The cost of producing a new type of “mousetrap” may exceed what people are willing to pay for it. If that is the case, we need to know! Then we will need to find out how to bring the costs under control in relation to market demand, develop market demand by showing its effectiveness, or develop a whole new “mousetrap.”

Learning to think like your niche customer is essential for effectively setting pricing that sends the best message to them. Mike knows his clients; most of them don’t own a meat grinder and handle their own meat processing. That’s not why they hunt or raise their own beef. They expect careful handling and an exceptional product delivered with outstanding service, knowing it won’t come at a bargain-basement price. Mike’s pricing structure feels right to his customers; therefore, Mike continues to enjoy a robust business with his niche market.

But for Mike to get pricing right, he needed to learn how to think like his niche customer. And that’s not how Mike usually thinks. He wouldn’t think of paying someone else to butcher for him. He enjoys the process. He has the tools and skills to do it. To Mike, butchering seems like a low-value service.

But Mike’s ideal customer doesn’t enjoy the process or have the tools and skills needed. Butchering for them is a problem to be solved, not a process to be enjoyed. The step of thinking like his customer thinks about price was difficult—he had to tell his own predispositions to lie down and be quiet. But when Mike understood how powerfully price communicates, he achieved deeper rewards.

Mike discovered that his hunting clients were willing to pay a lot for a skinning service, rather than doing it themselves. Mike’s clients don’t hunt because they want to skin deer; they hunt because they love the thrill and memories. They come to Mike’s because he knows how to package up their experience and deliver quality and flavor. It turns out that Mike can give his employees a bonus for every carcass skinned. Why? Because this function solves a messy problem for the customer, and they are willing to pay considerably more for this service than “costs plus.”

Mike was pleased when he learned how to create a product with very high value at a comparatively low cost. Instead of throwing scraps of high-quality meat into ground beef, Mike turned them into skewers with peppers, onions, and mushrooms. The skewers are extremely popular. A price aligned with the perceived value of grill-ready skewers helps them leave the shelves.

The brain responds subconsciously to both high and low prices.

Nothing shouts a louder message about your product than price. Conservative-minded businessmen tend to set the lowest prices possible. But consider carefully your potential customer. He may want exactly the level of service or product you provide, but a too-low price may turn him away. Conversely, he may want the economic and basic service, but a high price will push him elsewhere.

Quality Manufacturing and Coatings broke an industry barrier, tripling their output with only a slight increase in overhead. If they had dropped their prices to reflect these significant savings, their clients would not have suspected greater efficiency at the plant; they would likely have suspected inferior quality.

Mike knows that he is not the cheapest processor around. Larry’s Locker, just down the road, serves customers in a distinctly different style. It was set up after Mike had been in business for a while. Their message of lower prices attracted the customer whom Mike was finding increasingly difficult to serve effectively. The presence of Larry’s Locker actually helped Mike’s Meat develop its niche and focus. The way people respond to price was responsible for this screening.

When establishing pricing, the power of three conveys a unique message.

Providing three models or three levels of service gives the customer an intuitively tidy set of options to choose from. “High, medium, or low,” “gold, silver, or bronze,” and “deluxe, premium, or classic” are frequently used to categorize products and services with varying price tiers.

Three options make it easier for customers to compare the relative value of each because there are three data points instead of two. Some people gravitate toward the middle option as being not too high, and not too low, but just about right. Others gravitate to the low-priced option because they want to feel like they are saving money or getting a good deal. Or, perhaps they just want to get their feet wet with the least expense. Still others gravitate towards the high-priced option because they want the best.

Mike learned to utilize the power of three by offering family packs to customers purchasing meat in bulk. He offers three tiers of high-quality meat cuts: Bronze, Silver, and Gold. Each quality tier offers small, medium, and large sizes. This method helps people think, “Which would be best for me?” rather than immediately comparing to other buying options in the big wide world. Instead, they focus on where and how they fit into what was thoughtfully arranged.

Purposeful pricing requires thoughtfulness regarding discounts.

Mike is cautious about offering a percent-based discount off the retail price. He knows that while this is often done, businessmen can quickly deplete their profits. Discounting works against the bottom line to the same proportion as price increases help. Calculate the additional sales volume required to recapture all the dollars lost due to the discount. Without attentive computation, that “SPRING SALE! 30% OFF!” becomes a tire-spinning exercise—lots of motion, but none of it forward motion of the net profit type.

Here is a sample scenario of the math behind discounts. Suppose you have a 50% gross margin and discount the price by 25%, you need to double your sales to recover a 25% discount. Discounts can be extremely detrimental to your bottom line if you don’t understand how the numbers are working.

On the other hand, increasing prices incrementally typically does not have a detrimental effect on one’s business. First, assuming prices have not been raised recently, a 5% price increase usually has almost no detectable difference in sales volume. Secondly, if you have a 25% profit margin and increase the price by 25%, you can actually lose 50% of your sales and still net the same dollar amount! That’s because of the increased profits garnered from the price increase.

This does not mean you can be reckless when raising prices. Rather, you should calculate the potential results of price increases. The few customers that Mike loses during periodic price increases are typically those who least fit his niche in the first place. Mike isn’t a bargain-basement butcher. Besides, Mike doesn’t mind a little less work while making a little more money, especially when he’s up over capacity. Mike has learned that price increases aren’t as risky as he first thought.

Caution is necessary when operating in a commodity business. Unless you have a distinct advantage in the way you serve your customers, you will need to stay very close to market prices for products like grain, heating oil, or apples.

One other tip:

When setting prices, it is vital to understand the difference between markup and margin. Markup is the amount added to product cost in order to determine a selling price, while margin is how much of the selling price is profit.

A product’s markup and margin amounts should be the same, but the percentage for each is different. For example, if a product costs $8,000, a 25% markup of $2,000 ($8,000 times 25% equals $2,000) results in a $10,000 price ($8,000 cost + $2,000 markup).

In this example, the margin is also $2,000 ($10,000 minus $8,000), but the margin percentage is only 20% ($2,000 divided by $10,000). So, when someone says a 20% markup, you know that it is 20% of the cost, while a 20% margin is 20% of the price.

It is common to miscalculate profitability by confusing markup and margin percentages. From the example above, if you used a 25% markup, the price would be $10,000 per product. Let’s say you sold $20,000 of product. In this case, you might say, “My markup is 25%, so my profit on $20,000 must be $5,000” (25% of $20,000).

But that is incorrect—your profit margin on each unit is only $2,000 ($8,000 + 25%), so your total profit on the $20,000 sales is $4,000.

To avoid this confusion of mixing up percentages, it is best to use margin-based pricing. If you want a 20% margin, simply divide your cost by 100% – 20%.

In this example, you would divide $8,000 by 0.8 (1.00 – 0.20), and the resulting price would be $10,000. Now, when you sell $20,000, you can use the same 20% to calculate profit; 20% of $20,000 is $4,000—your profit.

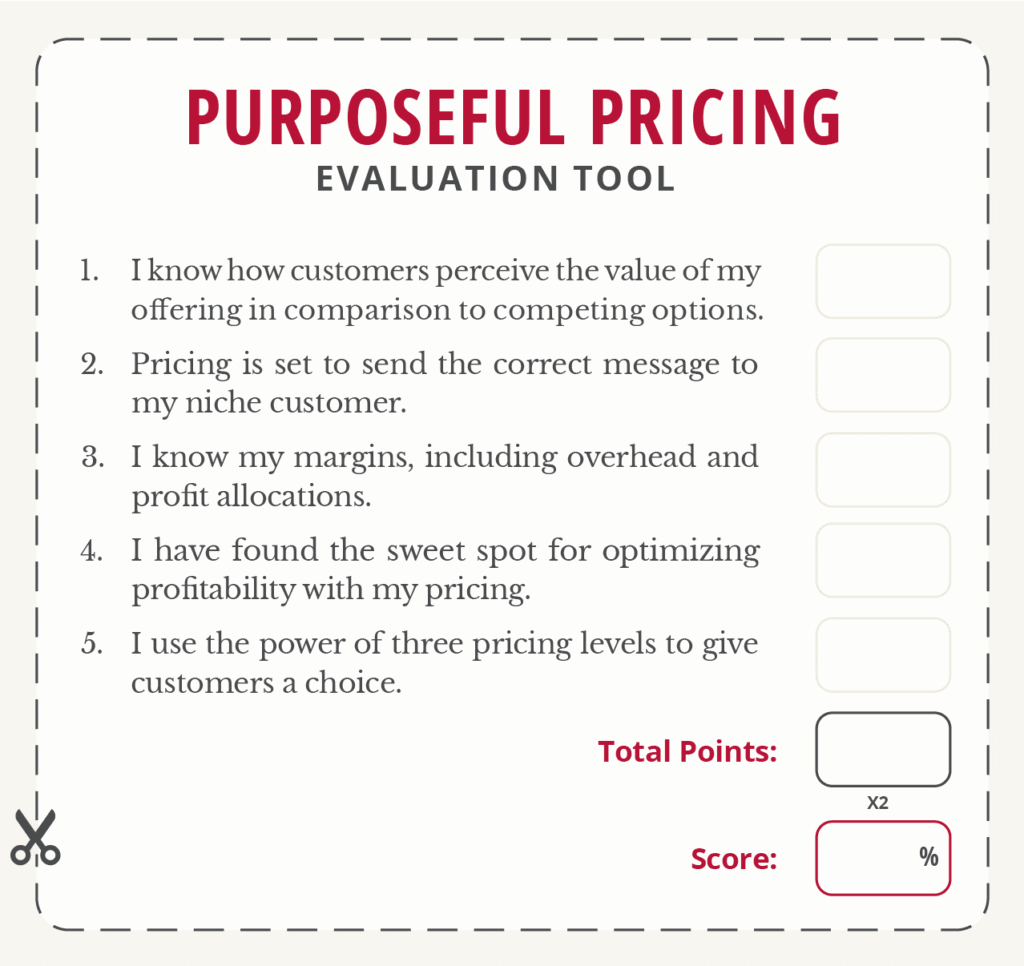

Evaluate your business

Here is an evaluation tool to help you assess your prices.